By Juliet Hollingsworth

Yesterday I walked past this tree, I noticed how entwined the branches were – like a tangled necklace. It made me think of the work I do with clients, how, so often it is a case of untangling the branches to find the trunk underneath. Many people do not know what is wrong, they just know they don’t feel right. There may be so many layers to peel back before the root cause is found.

Often people present with a specific complaint, but as we start to untangle the branches we realise that the issue is actually a symptom of something else. Stress is very often like this. People often say “I’m not stressed”, but there are so many possible symptoms, often they do not realise the reason their body is behaving in a certain way is due to stress.

April is stress awareness month, a much needed recognition of the growing amount of stress in all our lives. When I first started as a hypnotherapist over ten years ago, most of my clients wanted to lose weight, quit smoking or stop a habit. Over the past couple of years, most of my clients now want help with easing stress or anxiety.

Growing causes of stress?

Work pressures have increased, technology has increased life pressure and there are greater expectations of what we can achieve as individuals. I have heard others say:

We are expected to parent like we don’t have a job and work like we don’t have children.

We all want to cook from scratch, be vegan, or sugar free, but our busy lives push us to rely on convenience foods then feeling guilty for this. Online shops mean that we can order something in the evening to arrive the next morning – but this means we can spend three hours searching for the best deal. We should all exercise five times a week… but when?!

Technology

Technology is moving far too quickly for us human animals.

Our brain does not realise that we do not need excess adrenaline to run though our body just because we need to finish a piece of work for the end of the week.

Our heart doesn’t need to beat faster when our children need to be picked up from school at the same time we need to be in a work meeting.

Our blood pressure doesn’t need to rise because we feel obliged to research the best washing machine before buying.

Our muscles do not need to tense because we’ve read something on Facebook that gives us feelings of unease.

We do not need to feel the stress response because it’s 10pm and we haven’t done 10,000 steps.

But this is what often happens.

The physiology of stress

Stress is the body’s response to a dangerous situation. When our brain senses danger it responds to this by entering the “fight or flight” response. The brain is reacting quickly and effectively to save your life.

The nervous system floods your body with epinephrine (more commonly known as adrenaline) and cortisol.

Adrenaline impact

If I were to tell you that adrenaline is used in medical situations as a stimulant in cardiac arrest, as a vasoconstrictor in shock, and as a bronchodilator and antispasmodic in bronchial asthma, it would go some way to explain why there is such a severe reaction in the body when we feel stress.

Cortisol’s role

There are cortisol receptors all over the body, which indicates that cortisol plays a part in overall body health. It helps to regulate metabolism, control blood sugar levels, reduce inflammation and assist memory. Cortisol also has a controlling effect on salt and water balance, helping control blood pressure. During pregnancy cortisol supports the developing foetus.

However, alongside this, cortisol shuts down the systems of the body that are not needed when facing immediate danger, such as the digestive system and the reproductive system.

Fight or flight

The effects of adrenaline and cortisol on the body are increased blood pressure, faster breathing, tighter muscles, a racing heart and sharpened senses. All of this is intended to increase your strength and stamina, increase your focus and speed up your reaction time so that you can fight or flee from the danger in front of you. It is a valid and necessary response, but one which tends to be less vital in modern life.

The fight or flight response in the brain has not yet evolved to match our lifestyle. Not only this, but the brain reacts in the same way to a real or imaginary threat so is triggered far more often than needed.

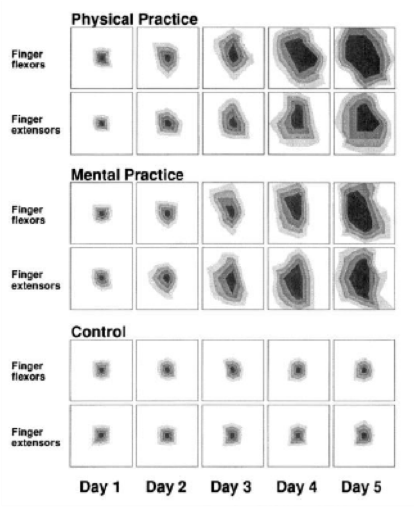

In 1995 a Harvard study (Pascual-Leone A, 2019) showed a similarity in how the brain reacts to real and imagined situations. The subjects in the study were asked to play a one handed, five finger exercise on a piano.

The first group were asked to physically perform the exercise for two hours a day for five days, whilst the second group were to do the same but in their imagination. The control group did not practise the exercise. TMS (brain stimulation) was used to show the effects on the brain. As you can see the physical practise and mental practise groups showed very similar results.

This knowledge should be taken into consideration when questioning why our body is behaving in a certain way. There are of course times when the fight or flight response is still needed — when we need to perform an emergency stop whilst driving, for example.

Positive effects of stress?

In other situations, the fight or flight response can help us; in sport to achieve great results, to achieve in situations that require preparation such as school exams or a presentation at work as the stress encourages us to prepare instead of do something more pleasurable. In some situations the fight or flight response can positively challenge us. BUT the first thing to consider is that we will (some people more than others) enter the fight or flight response when we do not need to.

There are times that our brain perceives a situation to be a threat to our life when it really is not. The second thing to consider is that our brain may do this even when the situation is imagined.

Prolonged stress

So simply put, stress is the body entering the fight or flight response because the brain has sensed imminent danger. The fight or flight response is designed to be a quick response to move us out of the face of danger quickly. We are not designed to stay in this physical state for a long period of time. However, as the perceived life-threatening event is very rarely life threatening, or short lived, we find ourselves spending, days, weeks, months in the fight or flight response.

Some of the effects of the body being in this state for so long are (HelpGuide.org, 2019):

- Memory problems

- Inability to concentrate

- Poor judgment

- Seeing only the negative

- Anxious or racing thoughts

- Constant worrying

- Depression or general unhappiness

- Anxiety and agitation

- Moodiness, irritability, or anger

- Feeling overwhelmed

- Loneliness and isolation

- Other mental or emotional health problems

- Aches and pains

- Diarrhoea or constipation

- Nausea, dizziness

- Chest pain, rapid heart rate

- Loss of libido

- Frequent colds or flu

- Eating more or less

- Sleeping too much or too little

- Withdrawing from others

- Procrastinating or neglecting responsibilities

- Using alcohol, cigarettes, or drugs to relax

- Nervous habits (e.g. nail biting, pacing)

So, what can we do about this?

Number 1

Recognise that we are suffering with something and we do not have to

Number 2

Accept that we may be living in the fight or flight response – a stressed state

Number 3

Find a way to help the brain understand that we are not in danger and seek support to help the body move out of the fight or flight response*

(*if you feel that you are in danger please seek the relevant support)

How therapy may help

There are a number of ways that therapy can help with the stress response. This ranges from techniques to help manage situations, to helping the brain recognise what is a danger and what isn’t, to relaxation techniques and tools to eliminate the stress response when it occurs.

Every course of therapy with me begins with a free, one hour, no obligation consultation. I ask a number of questions that give us both an insight into the situation. I can suggest the best way to work and you have the opportunity to ask any questions you may have.

If you would like to find out more or book your free initial consultation then please contact us at Oak Park Clinic.

References

HelpGuide.org. (2019). Stress Symptoms, Signs, and Causes. [online] Available at: https://www.helpguide.org/articles/stress/stress-symptoms-signs-and-causes.htm/ [Accessed 21 Mar. 2019].

Pascual-Leone A, e. (2019). Modulation of muscle responses evoked by transcranial magnetic stimulation during the acquisition of new fine motor skills. – PubMed – NCBI. [online] Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7500130 [Accessed 21 Mar. 2019].

Hormone.org. (2019). Cortisol | Hormone Health Network. [online] Available at: https://www.hormone.org/hormones-and-health/hormones/cortisol [Accessed 21 Mar. 2019].

Publishing, H. (2019). Understanding the stress response – Harvard Health. [online] Harvard Health. Available at: https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/understanding-the-stress-response [Accessed 21 Mar. 2019].

McEwen, Bruce S. “Central Effects of Stress Hormones in Health and Disease: Understanding the Protective and Damaging Effects of Stress and Stress Mediators.” European Journal of Pharmacology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 7 Apr. 2008, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2474765/.

Team, H. and Team, H. (2019). How is Anxiety Different from Stress? – Stress and anxiety. [online] Healthstatus.com. Available at: https://www.healthstatus.com/health_blog/depression-stress-anxiety/how-is-anxiety-different-from-stress/ [Accessed 28 Mar. 2019].